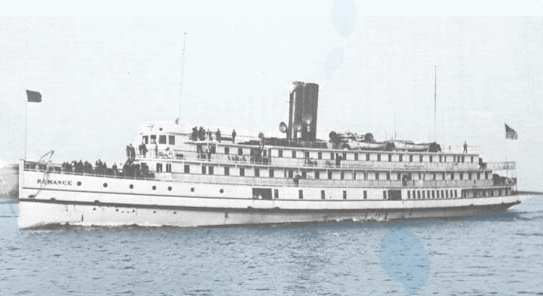

An old but fast excursion steamship, the S.S. Romance was entering Boston from Provincetown, when an outbound coastal steamer rammed her in the fog.

The outbound vessel, the SS New York, nearly cleaved the Romance in two on that foggy late afternoon of September 9, 1936.

The New York struck the Romance just aft of the pilothouse. With a crew of 52 and 208 passengers returning from a picnic in Provincetown, the 245-foot vessel sank in minutes.

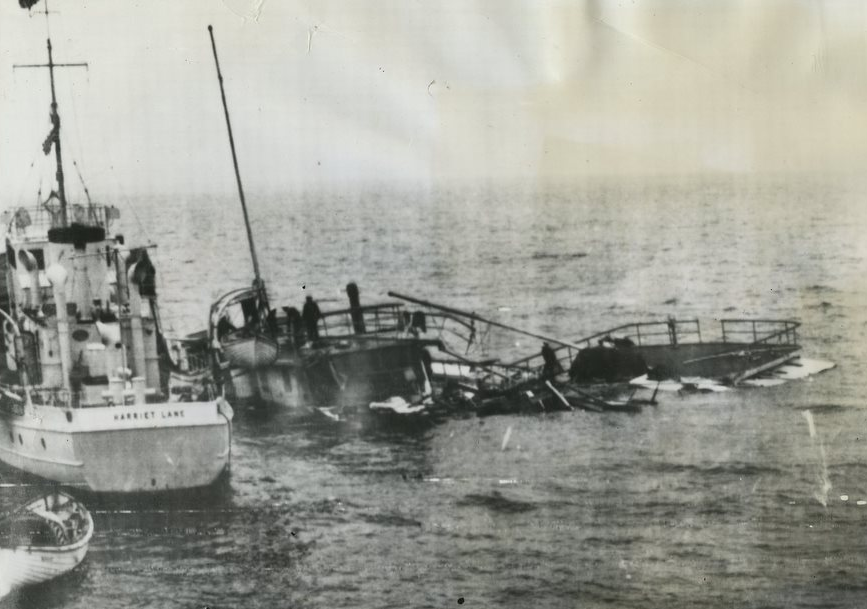

US Coast Guardsmen from the USCGC Harriet Lane search the floating wooden superstructure of the SS Romance for victims or survivors. The Boston-to-Provincetown steamship sank between Graves Light and Nahant in 1936. The steel hull sank, and the superstructure washed up on a local beach. (Graves Light Station collection)

All aboard were saved, thanks to the quick thinking and professionalism of the captains and crew of both vessels: Captain Adelbert Wickins of the Romance, and Captain Roland Litchfield of the New York.

Captain Litchfield’s decision to keep his vessel lodged into the hull of the smaller Romance prevented the stricken steamer from flooding and sinking before everyone could be saved.

A dramatic account of the rescue recalls, “In the finest traditions of the sea, Captain Wickens searched every place a passenger could be while Chief Engineer Joseph Martinez and Electrician Charles Roland manned their posts until the ship literally sank from beneath their feet.

“Fifteen minutes after the collision, her whistle still blowing its futile cry, Romance settled by the bow and slid beneath the waters of Massachusetts Bay, the mast head light glowing eerily beneath the waves as the steamer plunged to her final resting place.”

Graves Light Keeper Llewellyn Rogers witnessed the collision. Rogers was the last keeper from the US Lighthouse Service, and he witnessed the most wrecks, including the City of Salisbury (1938) and Mary E. O’Hara (1941).

Graves Light Keeper Llewellyn Rogers witnessed the collision. Rogers was the last keeper from the US Lighthouse Service, and he witnessed the most wrecks, including the City of Salisbury (1938) and Mary E. O’Hara (1941).

Romance was built in 1898 as the Tennessee, by Harlan & Hollingsworth in Wilmington, Delaware. The Bay State Steamship Company bought the Tennessee in 1935 and renamed her Romance for Boston-to-Provincetown excursions.

The wreck settled on the bottom of a busy channel off Nahant, about a mile north of Graves Light. It was crushed to keep it from being a navigational hazard. The bow and boilers remain partially intact, and the debris field still yields artifacts, according to Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions, because visibility is poor in summer and few divers visit the site. However, in colder months the visibility is 40-50 feet and makes for a good dive.

Metro West Dive Club calls the wreck “a junkman’s dream.”

Sources: Wrecksite.eu, Wreckhunter.net, Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs; MetroWest Dive Club, and Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions (which includes some excellent dive photos of the wreck).

The anchor that was aboard was salvaged By Fred Murphy, a Winthrop native. He want to the sight of the wreck with his sailboat and dove until he found it. It now sits in front of his Family home in Winthrop.

Thanks for the comment, Lee. It’s exciting to hear from people who know details about historical artifacts from Boston Harbor.