The dawn of the 20th century brought with it the age of the great steamships.

The dawn of the 20th century brought with it the age of the great steamships.

Although some merchants experimented with colossal wooden sailing vessels – such as Boston’s Palmer Fleet, with its 300-foot long, five-masted coal schooners – the age of steel-hulled steamships would transform the seaport.

Industrial revolution changes Boston Harbor

Demand grew for larger and faster ships to haul wealthy travelers, poor immigrants and industrial-sized cargo.

The first decade of the century saw the keel-laying of huge liners like the Cunard Line’s Lusitania and the rival White Star Line’s sister ships Olympic and Titanic.

Alhough those great ocean liners would never visit Boston, other big passenger and cargo vessels would. They crisscrossed the Atlantic, moved up and down the coast, and soon would sail to and from California and Asia through the brand-new Panama Canal.

Bigger ships required bigger channels – and both required Graves Light

To remain a major, competitive seaport, Boston had to widen and deepen its channels to accommodate more and larger ships.

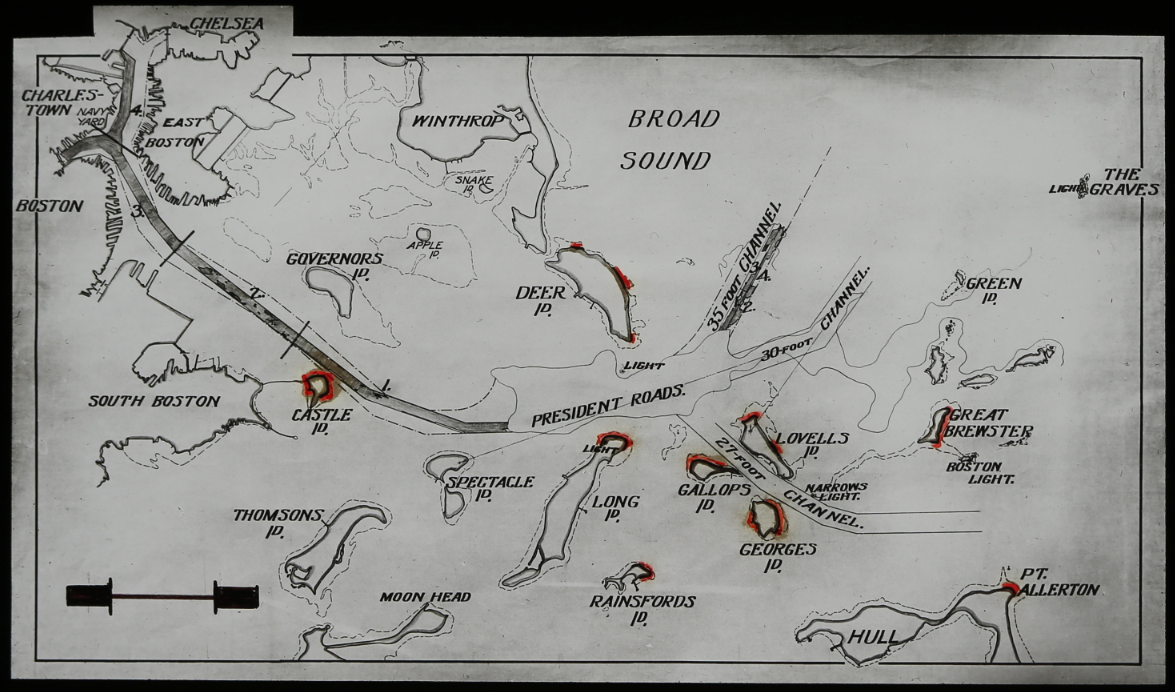

Bostonians dredged and blasted new channels in the northern part of Boston Harbor: the famous dual channels of Broad Sound among them.

That’s why Boston needed Graves Light: To mark the entrances to the Broad Sound channels to and from President Roads. Those channels lay between the treacherous Finn’s Ledge and The Graves.

Incredibly, some of Boston’s worst shipwrecks would occur after Graves Light was built.

Below is a copy of the original sketch for the design of the new channels, with the new Graves Light at the far right. We are grateful to the people at the Massachusetts Historical Society for providing us with these and other images of the development of Graves Light Station.

Bigger ships required bigger channels for Boston to remain a competitive seaport and to sustain the growth and economy of New England. Graves Light was required to help those ships navigate the new channels dredged and blasted by Broad Sound. (Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society