Artillery practice before World War II caused one shell to land too close to Graves Light, prompting the Superintendent of Lighthouses to issue a sternly worded letter to the Commanding Officer in Boston.

Artillery practice before World War II caused one shell to land too close to Graves Light, prompting the Superintendent of Lighthouses to issue a sternly worded letter to the Commanding Officer in Boston.

The 1937 incident was the only time the granite tower was ever shaken.

It happened on May 21 of that year, when the Army’s coastal defense force at Fort Banks in Winthrop practiced shelling Boston Harbor’s narrow outlet to the sea, apparently to ensure that they could strike at any enemy ships trying to enter the port.

The thunderous artillery practice had shattered the keepers’ dinner plates at Graves Light.

Fort Banks was home at the time to two batteries of huge Endicott 1890M1 mortars to defend Boston Harbor against enemy warships.

A total of 16 mortars provided a formidable defense for the harbor. Each mortar was 12-inch caliber, meaning that each fired an explosive shell 12 inches in diameter. Each shell contained between 700 and 1,046 pounds of explosives. Each mortar could hurl the shell between 7 and 9 miles.

A researcher at the National Archives in Washington has discovered carbon copies of the letters exchanged between the US Light House Service and the Department of War from May and June, 1937, settling a matter between the artillerymen and the Graves Light keepers.

The correspondence shows that at about 1:30 on the afternoon of May 21, 1937, the keeper at The Graves phoned his superintendent in Chelsea that during artillery practice from Fort Banks, one shell landed within 200 yards of the lighthouse.

That resulted in a phone call to the commanding officer at Fort Banks, who made sure it wouldn’t happen again.

It seems that no further incidents occurred, though the recorded correspondence, typed on manual typewriters and sent via the Postal Service, took some delays that in retrospect seem curious.

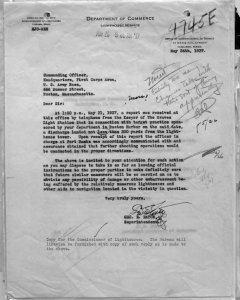

Three days after the incident, on May 24, Light House Superintendent George E. Eaton in Chelsea, sent a letter to the Commanding Officer of the First Corps Area responsible for Fort Banks. (Doc 1 May 24 1937)

Three days after the incident, on May 24, Light House Superintendent George E. Eaton in Chelsea, sent a letter to the Commanding Officer of the First Corps Area responsible for Fort Banks. (Doc 1 May 24 1937)

Eaton described the matter, making a correction about the distance of the target zone from the lighthouse.

Politely, but with what seems to be a taint of sarcasm, Eaton said that on receiving the phone call on May 21, “the officer in charge at Fort Banks was accordingly communicated with and assurance obtained that further shooting operations would be conducted in the proper direction.”

The lighthouse superintendent then spared no words to express his concern:

“The above is invited to your attention for such action as you may dispose to take in so far as issuing official instructions to the proper parties to make definitely sure that future similar maneuvers will be so carried on as to obviate any possibility of damage or other embarrassment being suffered by the relatively numerous lighthouses and other aids to navigation located in the vicinity in question.”

On the copy retained by the Commissioner of Lighthouses, someone scrawled in the margin, “Entirely too many chances taken with this sort of thing apparently.”

Three weeks later, on June 15, Colonel Clark Lynn, Adjutant General at Headquarters, First Corps Area in Boston, responded formally. (Doc 2 June 15 1937)

Three weeks later, on June 15, Colonel Clark Lynn, Adjutant General at Headquarters, First Corps Area in Boston, responded formally. (Doc 2 June 15 1937)

“No previous acknowledgement was made,” said COL Lynn, “due to the fact that your letter indicated that the Commanding Officer, Harbor Defenses of Boston, Fort Banks, Massachusetts, had been notified by telephone.”

The colonel assured the light house superintendent that instructions had been issued “to prevent any possible recurrence in the future.”

The same day he received COL Lynn’s letter, Superintendent Eaton wrote a memo to the Commissioner of Lighthouses, recounting the incident and stating that the Army commander “should have formally acknowledged our letter without request having to be made for the same.” (Doc 3 June 16 1937)

A modern Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) chart (fig. 4.2, p. 8) shows that the lighthouse crew was right to be upset: A surface explosion of 700 to 1,000 pounds of TNT would produce severe wounds from flying glass in a building 200 yards away.

The letters appear on this page. Click on each image to enlarge.