Big news, everybody. Graves Light received a little taste of a genuine first-order Fresnel lens, similar to the original 1905 lens that sent out a 350,000-candlepower beam across the harbor.

Big news, everybody. Graves Light received a little taste of a genuine first-order Fresnel lens, similar to the original 1905 lens that sent out a 350,000-candlepower beam across the harbor.

The Coast Guard is still in charge of the navigational aids at Graves, so we couldn’t make the beacon shine like it did before the original giant Fresnel lens was removed in 1975. Since 1905, Graves had been the most powerful lighthouse in New England. Not so any more.

So we did the next-best thing by reconstructing part of the lens with pieces from lighthouses around the world. We assembled them as part of the interior decor in a way that won’t interfere with the modern, solar-powered lamp.

What’s a first-order Fresnel lens?

John and Randy assemble the flash panels to adorn the kitchen on the watch deck.

For a lighthouse, a Fresnel lens is a beehive-shaped compound lens made up of rings of glass prisms that cast parallel beams of light.

It is named after its inventor, French physicist Augustin Jean Fresnel (1788-1827), who had a special understanding of the physics of light.

Lighthouse lenses are divided according to size and light focal length, a category called “order.” Formally there are eight orders of Fresnel lenses, with the first-order being the largest. (There is also a 3-1/2-order lens. Two larger lenses were ultimately developed.)

A first-order lens casts a beam that can be seen more than 20 miles away. Only the curvature of the Earth prevents it from shining further on a clear night.

Fresnel lenses are made of heavy glass prisms housed in large brass or bronze frames, assembled as panels and arranged in a circle. The entire assembly of an operating Fresnel lens rotated on mechanical carriage or a pool of mercury, and in some parts of the world, still does. That liquid heavy metal ensured steady, constant, friction-free rotation, regardless of the weather, on a corrosion-free surface. The Coast Guard recovered 400 pounds of mercury from Graves when it removed the lens. Our new lens is stationary and won’t be used as an aid to navigation, so there’s no rotation mechanism or mercury.

Where did the new Graves first-order Fresnel lens come from?

We assembled the new Graves lens from several antique first-order lenses from decommissioned or modernized lighthouses outside the United States. Nearly all first-order Fresnel lenses have been destroyed, or are owned by governments as legacy artifacts. No complete first-order Fresnel lens exists in private hands, anywhere in the world.

Working through Chance Brothers Lighthouse Engineers of Melbourne, Australia, we bought pieces from English lenses built between 1880 and 1920.

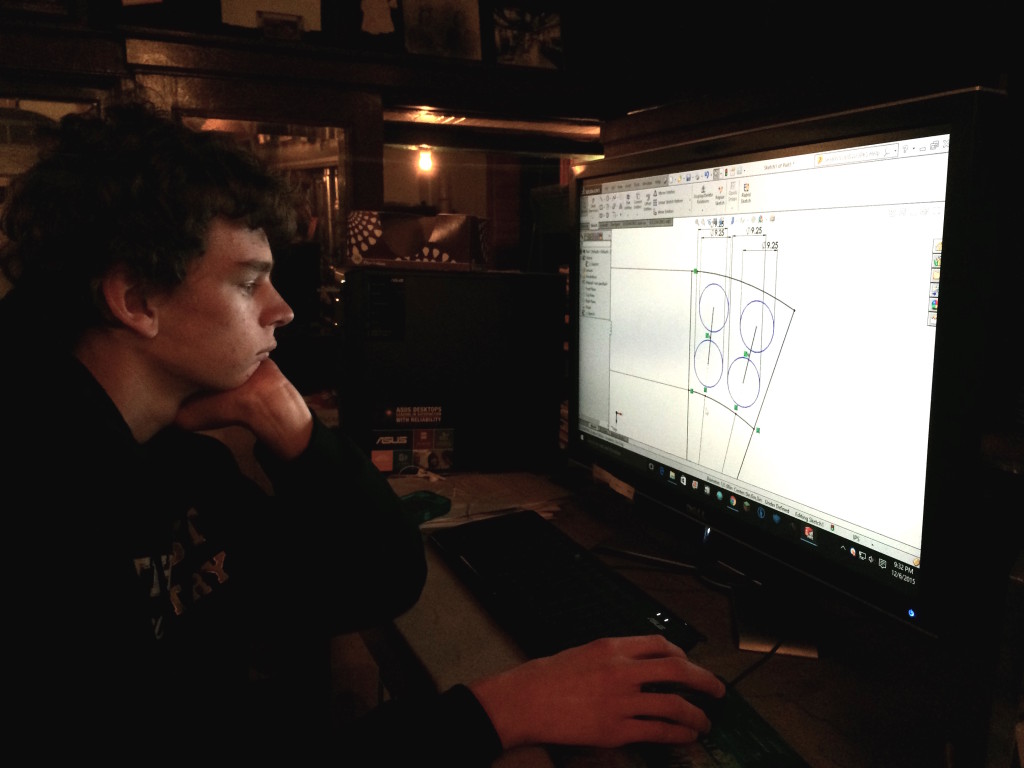

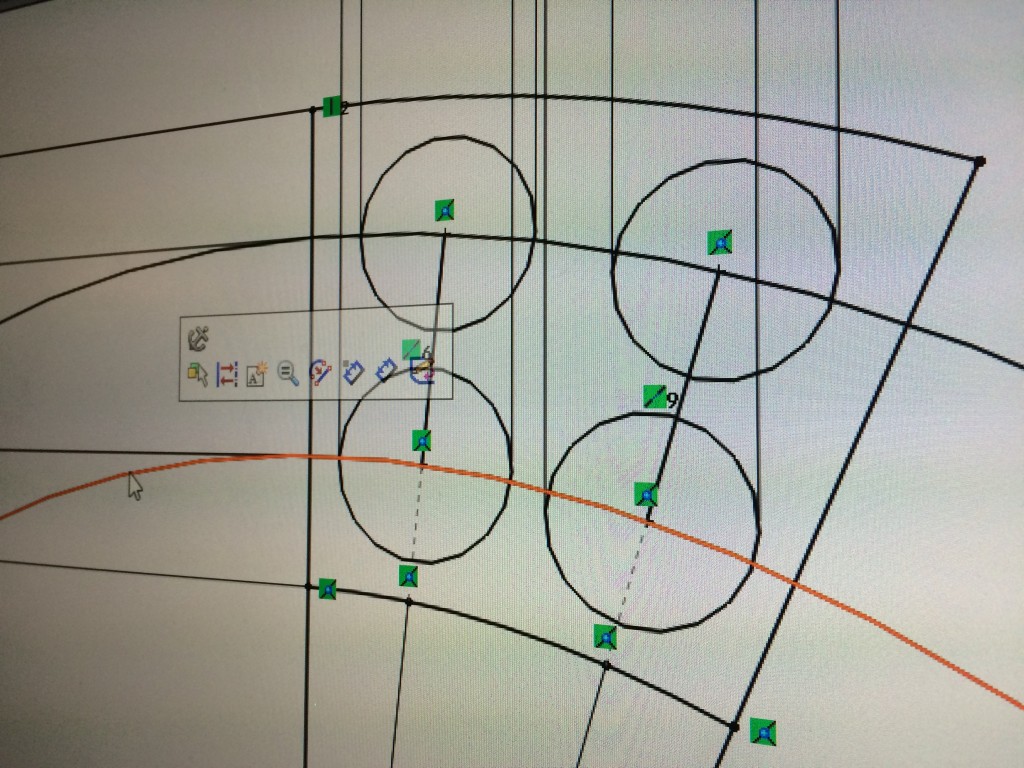

Wyatt designed the bronze frame by computer, and built a full-scale wooden mockup. Then he assembled the frame on the mainland to make sure everything fit.

Reconstructing a lens

A first-order Fresnel lens would generally consist of glass prisms assembled in about 45 panels.

The panels are stacked three high and arranged in a circle. The lower and upper panels are called catadioptric panels and bend the light by reflection like a mirror. The center sections, or flash panels, are dioptric prisms which concentrate the light like a magnifying glass.

We acquired glass prisms to fill 15 panels. For considerations of living space and climate control – and for the practical matter of finding enough prisms – we did not attempt to rebuild an entire first-order lens nor could we. These panels are so scarce, it appears there may be no more to be found!

The objective was to illustrate the wonder of a First Order lens without taking over our kitchen.

No shop drawings for assembling a lens like this exist. It’s been said the factories that made them in England and France were destroyed during World War II. Our own Wyatt designed a custom skeleton frame using SolidWorks software, and uploaded the specifications to a water jet cutter, producing a rigid structure out of 1/2-inch bronze plate.

The assembly in our shop allowed us to correct mistakes, make sure the glass prisms fit properly, and refine each frame to ensure a good fit-out on station.

We packed each completed panel in wooden crates, brought them to Graves Light aboard Miss Cuddy, and winched them halfway up the lighthouse to the entrance, and hand carried them up the tower for installation.

After assembly, we found that the lens focused sunlight inward and melted our first aid kit. We knew from our neighbor Sally Snowman, keeper of Boston Light, and our visit to the Castle Morro lighthouse in Havana, that the old Fresnel lens lighthouses had interior curtains to block the sun by day. Both the Boston and Havana lighthouses still have operational Fresnel lenses.

So we went to Zimman’s for a bolt of the proper cloth. Our own Keeper Lynn is creating a custom curtain to prevent the sunlight from starting a fire, without the curtain obstructing the navigational lamp.

Vital statistics

- Manufacturer: Chance Brothers of England

- Grade: First Order Lens

- Origin: From several lighthouses worldwide, circa 1880-1920

- Weight of a complete sense: 3 tons

- Weight of our lens apparatus: 1 ton

- Height: 9 feet

- Diameter: 6.5 feet

- Light strength: Approximately 350,000 candlepower with kerosene burner

Where’s the original?

The original Graves Light lens, made in Paris by Barbier, Bernard and Turenne, is in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. It isn’t on display, but is probably crated up in a warehouse. The Smithsonian loans out many of its pieces for public display, but federal law forbids the original Graves lens from being exposed to weather, so we couldn’t move it back to the lighthouse even if the Smithsonian would let us (which it won’t.)

The Coast Guard loans out Fresnel lenses under strict conditions, but requires that they be kept in climate-controlled environments, and, for preservation purposes, forbids them to be kept in lantern rooms.

See Theresa Levitt’s biography of optical genius Augustin Fresnel and his remarkable impact on lighthouses and navigation, A Short Bright Flash: Augustin Fresnel and the Birth of the Modern Lighthouse (Norton, 2013).

-

-

Dave and John haul up each lens panel.

-

-

Wyatt designed the bronze frame by computer, and built a full-scale wooden mockup.

-

-

Three sections assembled on land.

-

-

John and Randy assemble the flash panels to adorn the kitchen on the watch deck.

-

-

All finished! (For now)

-

-

-

A close-up of how we built the brass frame.

-

-

John, Dave, Joe, and Randy remove the 1970s lantern floor.

-

-

Jocelyn clears things up as we reach our final steps.

-

-

John Nelson and Randy Clark do the final fit.