This August marks the centennial of the first swimmers to Graves Light.

This August marks the centennial of the first swimmers to Graves Light.

We just discovered this today, when Carol went to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, to do some research.

She came back with articles from the Boston Daily Globe from August, 1914.

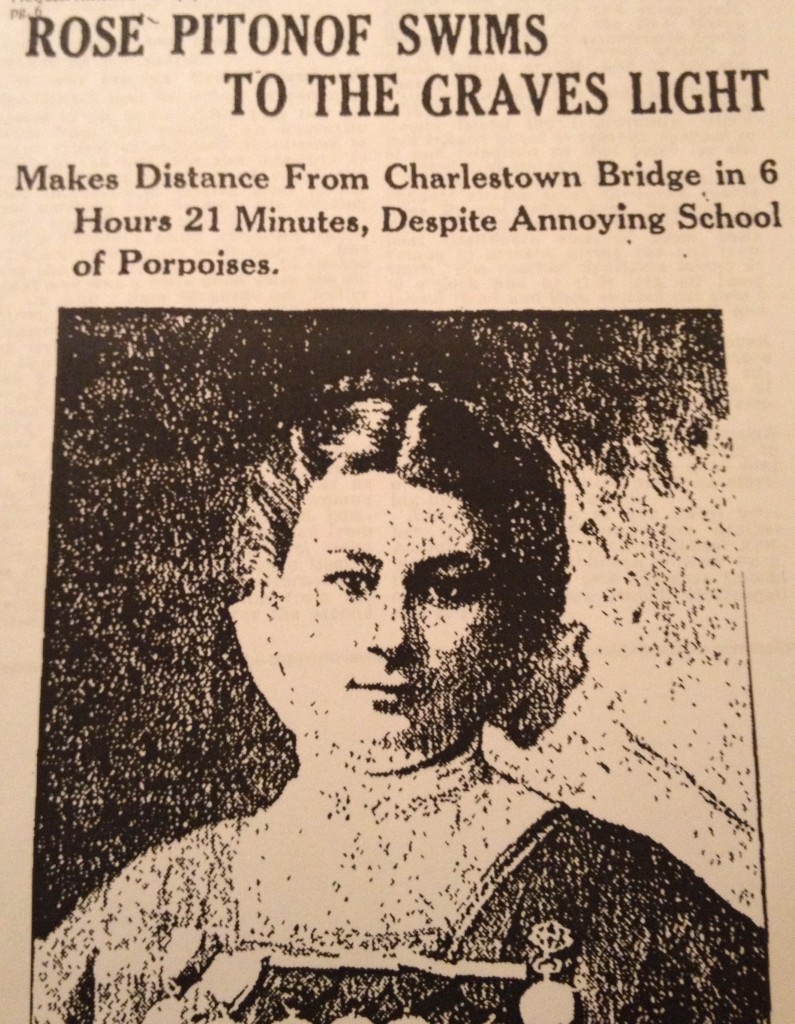

August 2 is the 100 year anniversary of the first men to swim to Graves Light. August 17 is the 100 year anniversary of the first woman to make the swim.

All of them swam 12 miles from Charlestown Bridge to The Graves.

The historic swimmers were Samuel Richards Jr., of the L Street Swimmers’ Club (better known as the L Street Brownies), who made the swim in 5 hours and 54 minutes; Henry Miron of Abington; George E. Hardy of Marlboro; and William R. Kessener, also of the L Street Swimmers’ Club.

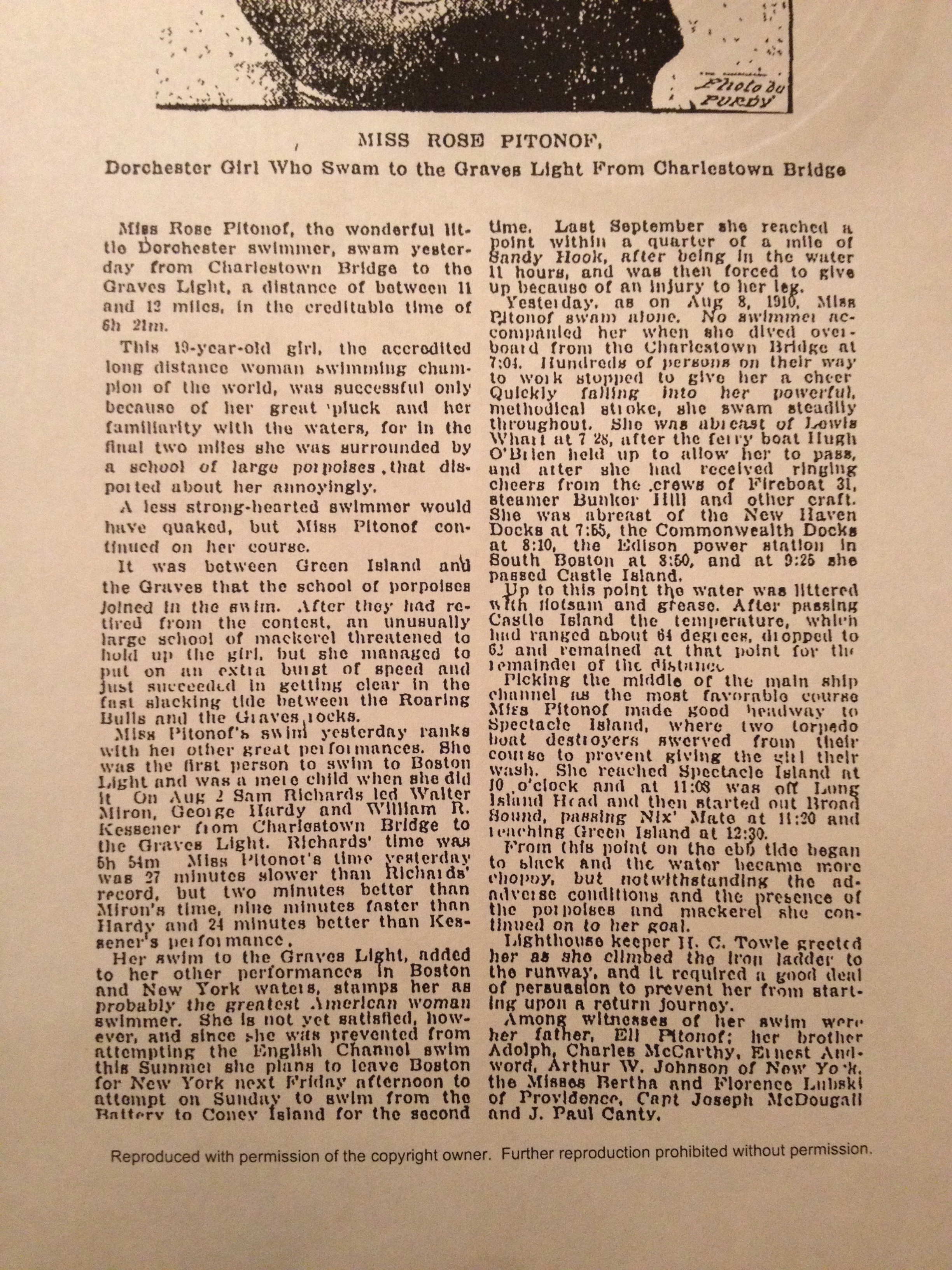

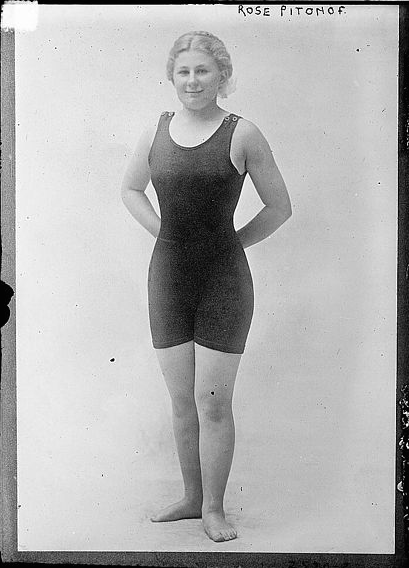

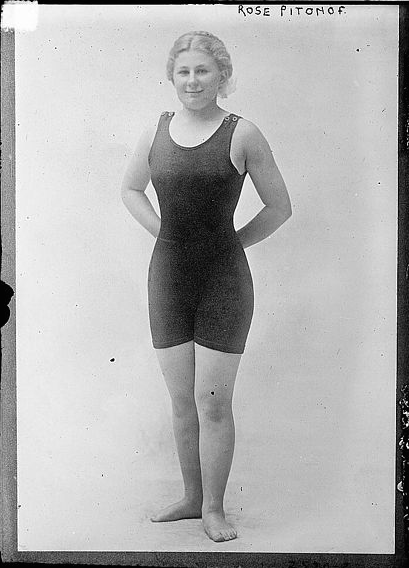

Just two weeks later, 19 year-old Rose Pitonof, whom the Globe called “the wonderful little Dorchester swimmer,” swam the same route in 6 hours and 21 minutes. Had she swum with the men, she would have placed second.

‘A feat never before accomplished or attempted’

Richards was a well-known distance swimmer, but his three colleagues were unknowns. Rose Pitonof was famous as a world-class distance swimmer, and had previously attempted to swim across the English Channel.

Rose Pitonof, in her swimsuit. (Photo via Wikipedia)

The swim to Graves Light was “a feat never before accomplished or attempted,” according to the Globe.

The four men swam at the same time but took different routes, with Richards allowing the tide, “which flowed through the Broad Sound Channel, to whisk him to his destination.”

Richards had decided to make the swim just the Saturday before. Hardy had planned to swim only to Boston Light. Miron, age 18, swam at a “fresh water pond at Abington,” and decided to swim to Boston Light when he heard of Hardy’s plans. He had tried but failed to swim to Boston Light two years earlier, in 1912. Kessener apparently planned the swim as a member of the L Street club with Richards.

Hardy started the swim before the others, “because he swims almost entirely with a breast stroke,” the Globe reported in a lively, blow-by-blow report.

During his swim, Richards was thinking about a planned date that evening with his wife and a group of friends, aboard the Harriet, “to take dinner at Boston Light, six miles away.” He reportedly considered the Graves swim as preparation for a planned swim across the English Channel.

“It was a great day’s outing for the swimmers, and opened up a new course for distance swimmers that may supplant the shorter, but more difficult course to Boston Light,” according to the Globe.

After arriving at Graves Light, Miron and Hardy were immediately welcomed as the newest members of the L Street Swimmers’ Club.

‘Annoyed’ by porpoises and mackerel

‘Annoyed’ by porpoises and mackerel

Miss Pitonof was considered “the accredited long distance woman swimming champion of the world,” the Globe reported, “successful only because of her great pluck and her familiarity with the waters, for in the final two miles she was surrounded by a school of large porpoises that disported about her annoyingly.”

“A less strong-hearted swimmer would have quaked,” according to the Globe.

The porpoises joined Miss Pitonof between Green Island and the Graves, and lost interest in the plucky swimmer after a while. Then “an unusually large school of mackerel threatened to hold up the girl, but she managed to put on an extra burst of speed and just succeeded in getting clear in the first slacking tide between the Roaring Bulls and the Graves Rocks.”

The Globe gave a lively and colorful account of the swim, which Miss Pitonof made alone, and through waters described as “littered with flotsam and grease.”

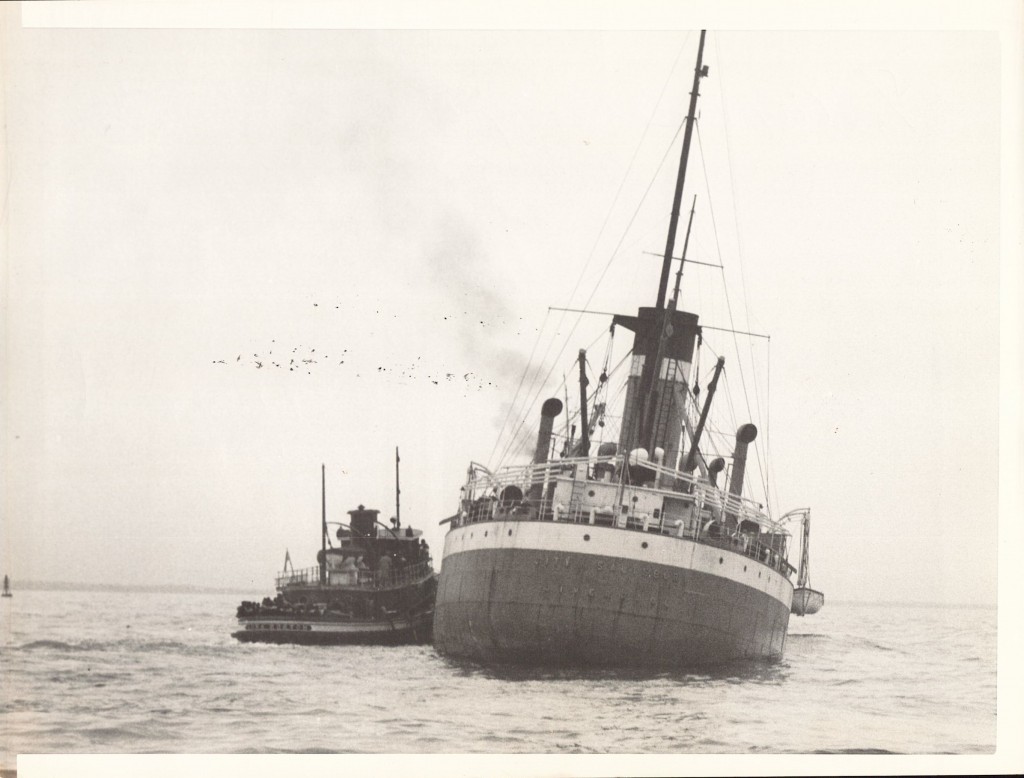

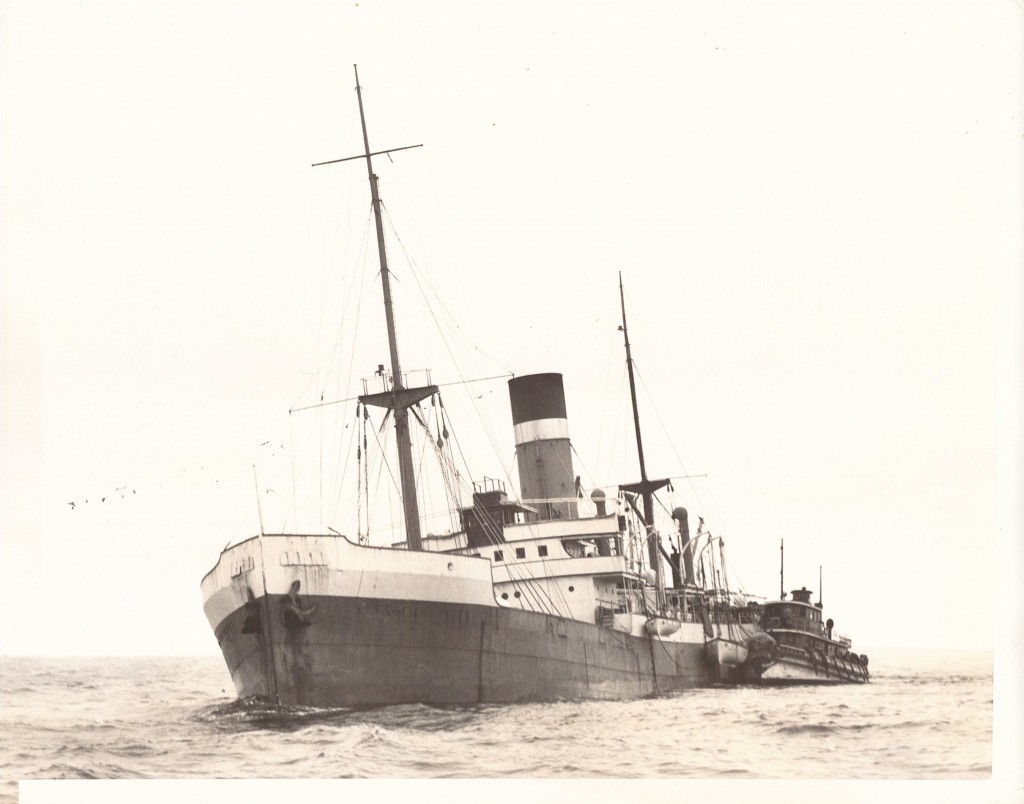

Hundreds of people on their way to work stopped at Charlestown Bridge to cheer. The ferry boat Hugh O’Brien slowed by Lewis Wharf to allow her to pass. The crews of Fireboat 31, the steamer Bunker Hill and other vessels sent up “ringing cheers.” Two torpedo boats “swerved from their course to prevent giving the girl their splash.”

Rose Pitonof tried several times to swim the English Channel, and became a Vaudeville performer. She married a local dentist and raised a lively family, and passed away at age 89 in 1984.